An article this week in The New York Times highlights the extraordinary measures some companies will take to avoid responsibility for their own actions. According to the newspaper, “General Mills, the maker of cereals like Cheerios and Chex as well as brands like Bisquick and Betty Crocker, has quietly added language to its website” that strips consumers of their right to sue the company for actions as simple as downloading a coupon or ‘liking’ the company or its products on Facebook.

Even more extraordinary, the paper reports: “In language added on Tuesday after The New York Times contacted it about the changes, General Mills seemed to go even further, suggesting that buying its products would bind consumers to those terms.”

The website language requires disputes with the company to be settled through arbitration rather than in the courts. Arbitration clauses have been common in the financial industry for decades but have steadily crept into other areas of American life in recent years. Large companies prefer arbitration because, unlike a trial, it is not open to the public and because the process, while supposedly fair, tends to favor deep-pocketed businesses. Since a 2011 Supreme Court ruling upholding the use of arbitration clauses in cellphone contracts this legal device has spread rabidly through the corporate world.

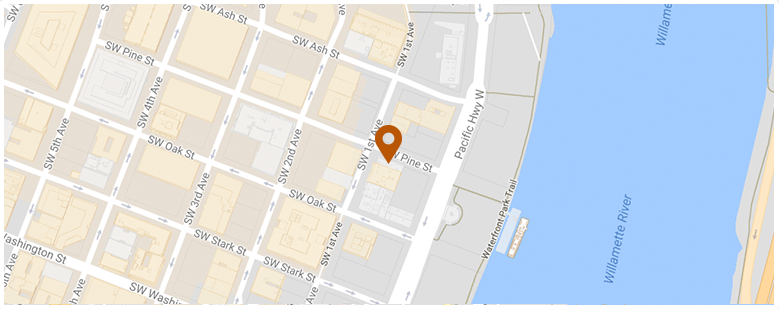

Oregon Injury Lawyer Blog

Oregon Injury Lawyer Blog