I have written on several previous occasions about corporate America’s systematic attacks on the class action system. A recent news item from the Associated Press offers a positive reason to revisit this topic. As the news agency writes, the huge insurance company State Farm reached a settlement earlier this month “in a federal class action lawsuit claiming the company funneled money to the campaign of an Illinois Supreme Court candidate.”

The preliminary $250 million settlement has its roots in a 1999 case that went against State Farm “for its use of aftermarket car parts in repairs.” Thousands of policyholders had sued the company alleging that its decision to pay for used (“aftermarket”) rather than new car parts when carrying out repairs on their vehicles violated the terms of the company’s contracts with customers. State Farm lost the original 1999 case and was facing the prospect of a $1.06 billion judgement against it. The company appealed, which is obviously it’s right and a reasonable thing for it to do. What was not right and proper was for the company to attempt to fix the final result of that appeal.

With the case making its way toward the Illinois Supreme Court, State Farm allegedly poured money into the campaign of a candidate for chief justice who, once elected, provided the key vote to reverse the trial court’s decision. In 2005 “the court ruled that the nationwide plaintiff class was improperly certified… It also contended using aftermarket car parts was not a breach of State Farm policyholders contracts.”

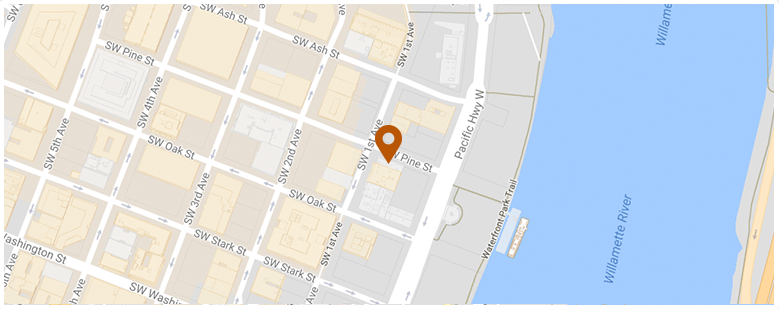

Oregon Injury Lawyer Blog

Oregon Injury Lawyer Blog