In a recent article in the New York Times Dr. Robert C. Cantu, a professor of neurosurgery at Boston University, issued a thoughtful, yet passionate, call for parents and school officials to rethink the way we approach youth sports here in the United States.

Writing that he meets with some 1,500 concussion patients each year, Dr. Cantu lays out the case for lowering the degree and intensity of contact that younger children experience across a range of sports. “In light of what we now know about concussions and the brains of children,” he writes, “many sports should be fine-tuned.” Dr. Cantu writes that children under 14 are fundamentally more vulnerable than older teenagers or adults. “A child’s brain and head are disproportionately large for the rest of the body,” he notes. “And a child’s weak neck cannot brace for a hit the way an adult’s can. (Think of a bobblehead doll.)”

He begins the piece by focusing on football, where he believes tackling should be eliminated for children under 14, but emphasizes that head trauma, concussions and brain injuries are all more common in other sports than is popularly believed. His piece goes on to propose rule changes in soccer, ice hockey, baseball, softball, field hockey and girls’ lacrosse – many of which are not activities most of us think of as contact sports.

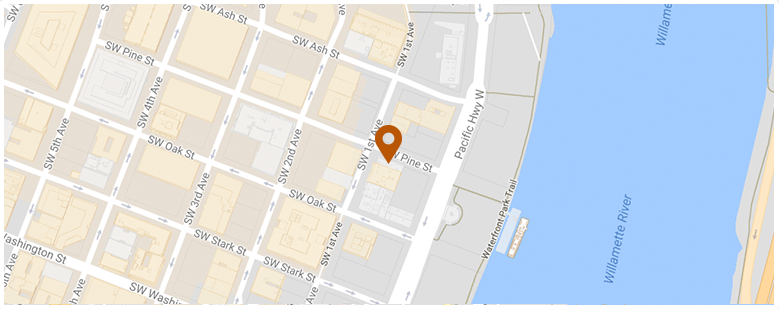

Oregon Injury Lawyer Blog

Oregon Injury Lawyer Blog