Last week the retired sheriff of Norfolk, Virginia was arrested and charged with numerous counts of bribery, according to The Washington Post. The newspaper reports Robert McCabe is accused “of taking cash, a loan, travel, gifts and campaign contributions from contractors providing food and medical care at the city jail” over the course nearly a quarter-century as the county’s chief law enforcement officer.

Along with the former sheriff, the founder of a Tennessee company that is part of the private prison and prison services industry was also arrested. The Post reports the Norfolk contract for prison medical services “was worth more than $3 million a year” and the company in question, Correct Care Solutions (now known as Wellpath), “continues to provide medical care at the Norfolk jail.” In exchange for the bribes the sheriff allegedly negotiated with Correct Care’s founder outside normal channels “and instructed employees to give his company inside information on potential contracts, including confidential bids from competitors”

This case caught my eye for two reasons. First, it is yet another example of what is wrong with our system of contracting prison management out to private corporations. Prisons are an unpleasant part of life, but they are also a public trust. It is essential that they be run in both a humane and accountable way, something that is fundamentally at odds with placing management or essential services – such as medical care – in the hands of companies primarily interested in making profits.

Second, that tension between legal and moral duties on the one hand and financial obligations to shareholders also reminds us why prison stories like this one are properly treated as civil rights issues.

As I have noted in this space on several previous occasions, a near-unanimous Supreme Court ruling more than 40 years ago (Estelle v Gamble; 429 US 97 (1976)) declared prisoners have a constitutional right to adequate medical care. That case established medical neglect is a form of “cruel and unusual punishment” and, therefore, prohibited by the Constitution.

The other key legal doctrine that applies in this case is “1983 law” – a reference to 43 USC 1983. This section of federal law states that all government jurisdictions (city, county or state, for example) are required to give people in their custody the civil rights to which they are entitled under the United State Constitution. This key civil rights protection ensures that Americans are not caught inside a two-tier justice system where local courts ignore rights that we all take for granted. Another important, but often overlooked, aspect of 1983 cases is the fact that they make it difficult for local officials to evade accountability by claiming governmental immunity. They also take precedence over any states laws that enforce caps on damages. These cases also provide for attorney fees should the plaintiff prevail.

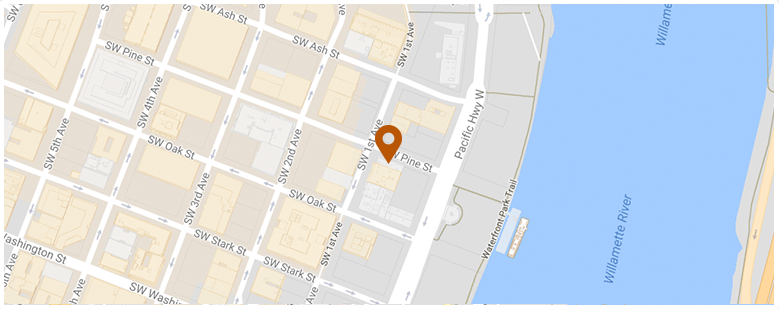

All of this reminds us that civil rights are not something that can neither be dismissed by those in power nor should they be taken for granted by the rest of us. Our courts are a powerful tool for people who the system has failed, as a Portland lawyer with experience in prison and jail abuse cases I understand how crucial it is for people to know their rights.

Washington Post: Former Norfolk sheriff accused of taking bribes for jail contracts

Cornell University Legal Information Institute: 42 USC 1983

Justia.com: Estelle v Gamble (429 US 97 (1976))

Oregon Injury Lawyer Blog

Oregon Injury Lawyer Blog