Last week marked a significant moment in the ongoing discussion about football, especially professional football, and concussions. As the New York Times notes, “after years of denying or playing down a connection, a top NFL official acknowledged at a hearing in Washington that playing football and having CTE were ‘certainly’ linked.”

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, is a degenerative brain disease that has increasingly been linked to former athletes in football and other contact-intensive sports. It “is believed to cause debilitating memory and mood problems,” the paper reports. Concerns about CTE are sometimes confused with equally serious concerns about sports-related concussions. Though the problems are related they also differ in fundamental ways. Concussions and other traumatic brain injuries are usually linked to single incidents where a blow to the head may cause problems that last for days or even weeks, and which can grow more intense if a person suffers repeated concussions.

CTE is thought to grow out of repeated blows to the head over long periods of time – including blows that individually do not cause concussions or concussion-like symptoms but whose cumulative effect can lead to long-term mental and physical issues. Last week’s Times story focuses on explaining the difference between the two and highlighting the degree to which CTE science “remains in its infancy.”

The piece quotes a doctor at the American Academy of Clinical Neoropsychology in Boston (which houses the largest brain tissue repository in the world) saying that parents regularly come to her afraid that a single concussion has left their child with permanent brain damage. “There’s no basis for that,” she says. Unfortunately what is also unclear is exactly how much head trauma and of what exact type over what period of time is required to set CTE in motion. It notes, for example, that doctors studying the disease describe it in “stages” similar to the progression of cancer, despite not being sure of the extent to which those stages coincide with known CTE symptoms.

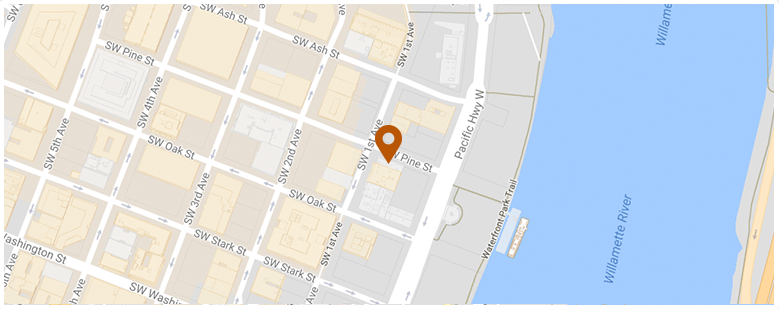

It is, in short, a malady about which we do not yet know enough – but against which we can still take precautions. As a Portland TBI and head trauma lawyer what stands out to me about the article is the responsibility that CTE throws back on coaches and school administrators. As we learn more and more about the dangers associated with repeated, seemingly minor, blows to the head many high schools, youth leagues and a few colleges have begun to alter the way they structure athletic practices. The youngest soccer players, for example, are not allowed to head the ball. Some high schools and colleges have severely restricted the use of full-contact tackling in football practices. The most important lesson that comes through from the Times article is simple but clear: until we know more about CTE parents and school officials alike are best-advised to find more ways to minimize head trauma at all levels of sports.

New York Times: On C.T.E. and Athletes, Science Remains in Its Infancy

Oregon Injury Lawyer Blog

Oregon Injury Lawyer Blog