It is getting warmer, which is always a good thing, but the spring also brings dangers – sometimes dangers that may not seem immediately obvious.

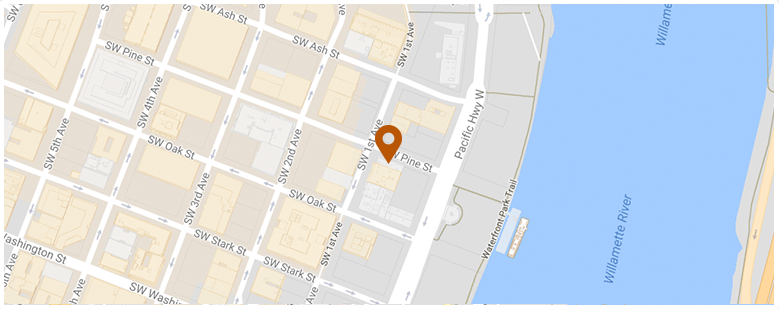

I’d like to focus today on water safety, a topic that regular readers will know I have addressed in the past. As a recent article in The Oregonian outlines the temptation to cool off in Oregon and Washington’s rivers at this time of year needs to be accompanied by some simple but important safety precautions.

“Entering cold water can cause swimmers to gasp, inhale water and then go under,” the paper notes. “Currents can keep swimmers from reaching safety.” The key thing to remember is that even on a hot day the water can be very cold. This is something most of us intuitively understand when it comes to the ocean, but which can be easy to forget where rivers are concerned. It is especially important since rivers, with their fast-flowing currents and other obstacles such as rocks and trees, are often even more dangerous than swimming at the beach.

Oregon Injury Lawyer Blog

Oregon Injury Lawyer Blog